Quant never predict... They quantify uncertainty!

Why serious quants think in distributions, not forecasts

It’s a sentence everyone has heard. It sounds smart. It is often misunderstood.

Many people take it to mean that quants refuse to say anything about the future. Others use it as a kind of intellectual shield, a way to avoid being wrong. Both readings miss the point.

The issue is not prediction itself.

The issue is believing that a single prediction can be treated as truth.

This distinction matters because markets are not difficult just because they are noisy. They are difficult because they punish certainty far more than they punish error.

This is what this newsletter is about. Not repeating a slogan, but explaining what experienced quants actually do when they say they “quantify uncertainty.”

1. The real problem is not prediction, but believing in a prediction

Prediction is not the enemy.

When people say “the market will go up” or “this strategy works”, they are not just making an estimate. They are implicitly choosing a single future and treating it as if it were reliable.

Even when numbers are involved, the mental model is usually the same. One central scenario. One expected outcome. Everything else pushed to the background.

The human brain is very good at constructing a coherent story. It is much worse at holding multiple incompatible futures at the same time.

This is where most mistakes start.

Not because the forecast is wrong, but because its uncertainty is ignored.

A trader who knows they can be wrong by a wide margin will size positions differently, manage risk differently, and survive longer. A trader who believes their prediction will hold tends to discover the tails the hard way.

For a quant, the question is never “what will happen?”.

It is “how wrong can I be, and what happens to my system when I am?”.

2. What experienced quants do instead

An experienced quant replaces a point estimate with a distribution.

This is a critical shift. Not cosmetic. Structural.

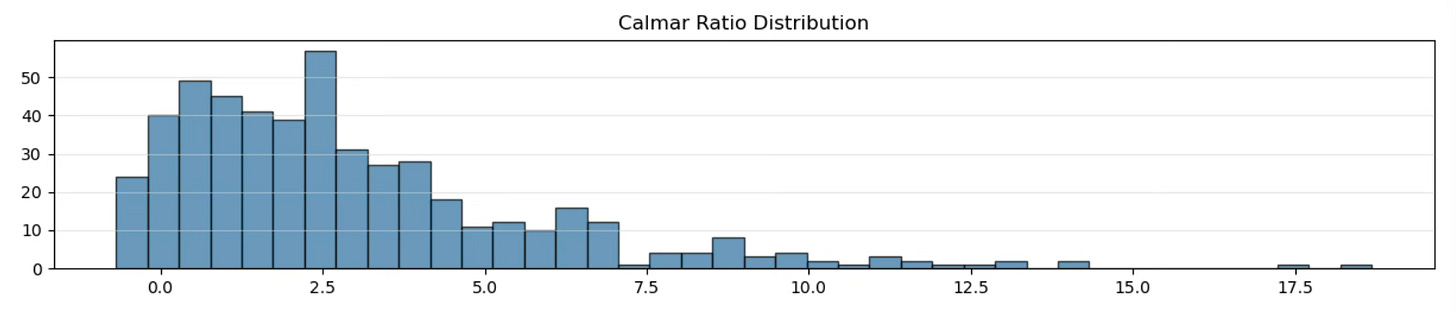

A single metric, a Sharpe ratio, a Calmar ratio, a CAGR, always looks clean in isolation. It gives the illusion of precision. But taken alone, it tells you almost nothing about how fragile the result is.

One number cannot tell you whether performance is repeatable or accidental.

It cannot tell you whether the strategy is robust or just lucky once.

This is why mature quant workflows never stop at a single backtest outcome. They generate distributions of outcomes.

Different subsamples. Different start dates. Different regimes. Different perturbations.

What matters is no longer the best result, but the shape of the distribution.

Is performance concentrated around a stable core, or carried by a few extreme runs?

Are drawdowns consistently manageable, or occasionally catastrophic?

Does the strategy degrade gracefully, or collapse when conditions shift?

A strategy with a lower average metric but a tight, well-behaved distribution is often far superior to one with a spectacular headline number driven by lucky randomness.

This is what quantifying uncertainty looks like in practice.

You stop asking “how good is this strategy?” and start asking “how often does this strategy behave acceptably?”

Once you see the distribution, you cannot unsee it.

And from that point on, single-number metrics feel dangerously incomplete.

3. Why this matters in real trading and machine learning

In trading, an edge is not a guarantee.

It is a small statistical bias that only exists under specific conditions.

A machine learning model does not “predict” the market. It outputs a conditional estimate based on past data. Treating that output as a forecast is where most mistakes begin.

What really matters is not average accuracy. It is how the model behaves when it is wrong.

Take a simple example.

Two strategies show the same Sharpe ratio on a backtest. One delivers steady, repeatable performance across many subsamples. The other makes most of its profits in a handful of runs and collapses in the rest.

On paper, they look identical. In reality, one is robust. The other likely driven by luck or highly risky.

This is why experienced quants care more about distributions than point metrics. They want to know how often a strategy behaves acceptably, not how good it looks in the best case.

“A model is not a crystal ball. It is a noisy sensor in an unstable environment.

The goal is not to remove uncertainty. The goal is to build systems that can live with it.”

Quantifying uncertainty is not about being cautious. It is about being realistic.

Markets are not difficult because they are unpredictable. They are difficult because they punish systems that are built around fragile assumptions and single-scenario thinking.

Experienced quants do not avoid prediction out of intellectual modesty. They move past it because they understand that robustness matters more than being right, and that survival comes before precision.

Once you start thinking in distributions, your entire process changes. How you backtest. How you size risk. How you interpret models. How you react when things break, which they inevitably do.

👉 If you want to go deeper into each step of the strategy building process, with real-life projects, ready-to-use templates, and 1:1 mentoring, that’s exactly what the Alpha Quant Program is for.