Bayes in Trading (3/3)

Bayes in practice. What actually matters for rare-event signals

In the previous newsletters, we applied the exact Bayes computation for a rare-event trading signal.

Now, instead of adding more math, we will vary the key parameters one by one and observe what really moves the probability that a signal is correct.

The goal is simple: identify which levers matter in practice, and which ones are often overestimated.

For reference, the model parameters are fixed to the same values as in Bayes in Trading (2/3):

The event occurs 2% of the time. P(E)=2%.

When the event is present, the model detects it 90% of the time. P(S∣E)=90%.

When the event is not present, the model still triggers a signal 12% of the time. P(S∣E bar)=12%.

In the following sections, each parameter will be varied one at a time to isolate its effect.

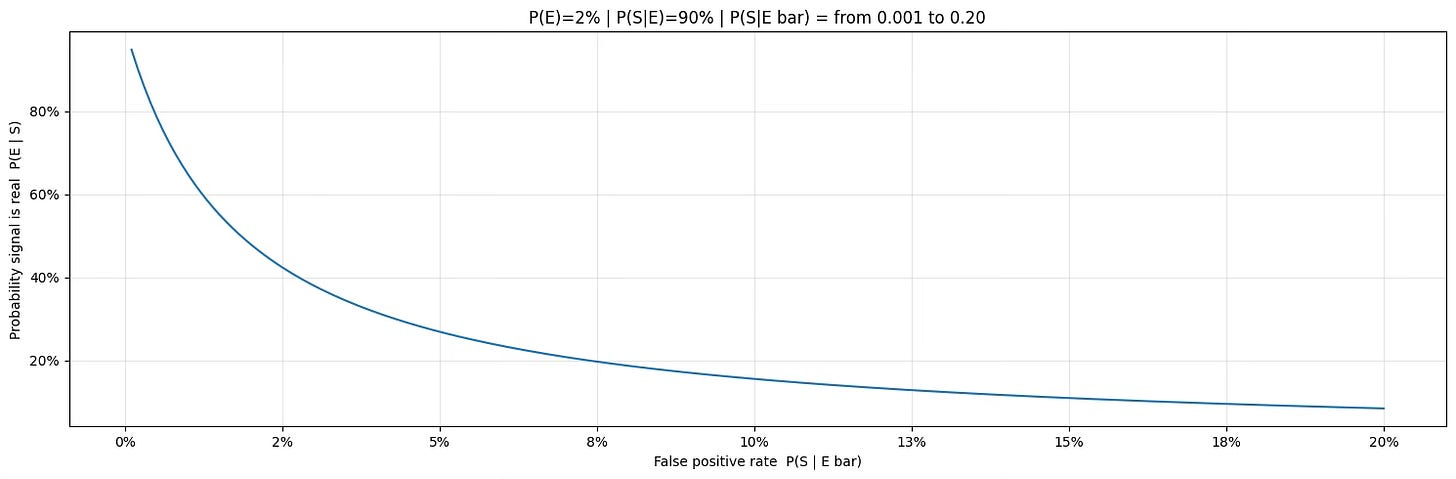

1. False positives dominate everything

This first plot isolates the impact of the false positive rate, while keeping all other parameters fixed. The effect is immediate and severe. Even small increases in P(S∣E bar) lead to a sharp collapse in the probability that a signal is actually correct.

When the event is rare, most observations belong to the “no-event” regime.

As a result, false positives quickly outnumber true signals, even if the model performs well when the event is present.

This is why many strategies fail not because they miss opportunities, but because they trigger too often when nothing is happening.

Reducing false positives is usually far more important than improving accuracy.

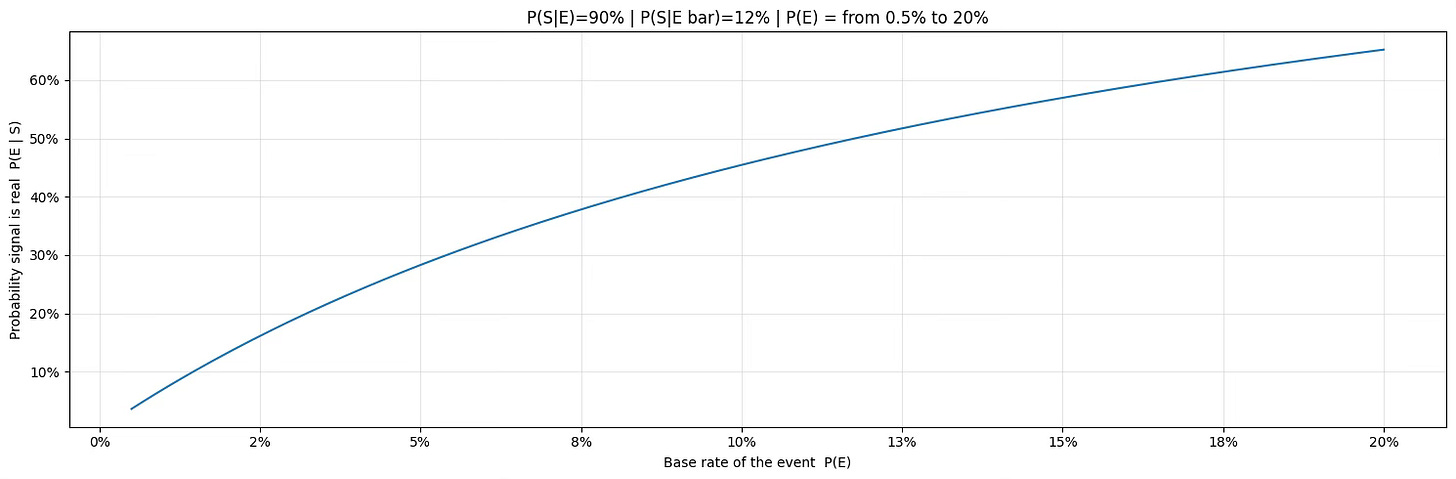

2. Event rarity is a structural constraint

In this second experiment, we keep the model behavior fixed and vary only the frequency of the event itself. The detection accuracy remains at 90%, and the false positive rate at 12%, exactly as before. Only the base rate P(E) changed.

The result is unambiguous.

When the event is extremely rare, even a well-behaved model produces signals that are mostly noise. As the event becomes more frequent, the same model suddenly appears far more reliable.

Nothing about the model changed. Only the market context did.

This highlights an important limitation of rare-event strategies.

Below a certain frequency, signal quality is structurally capped, regardless of how good the classifier is.

Sometimes the main problem is not the model, but the rarity of the event being traded.

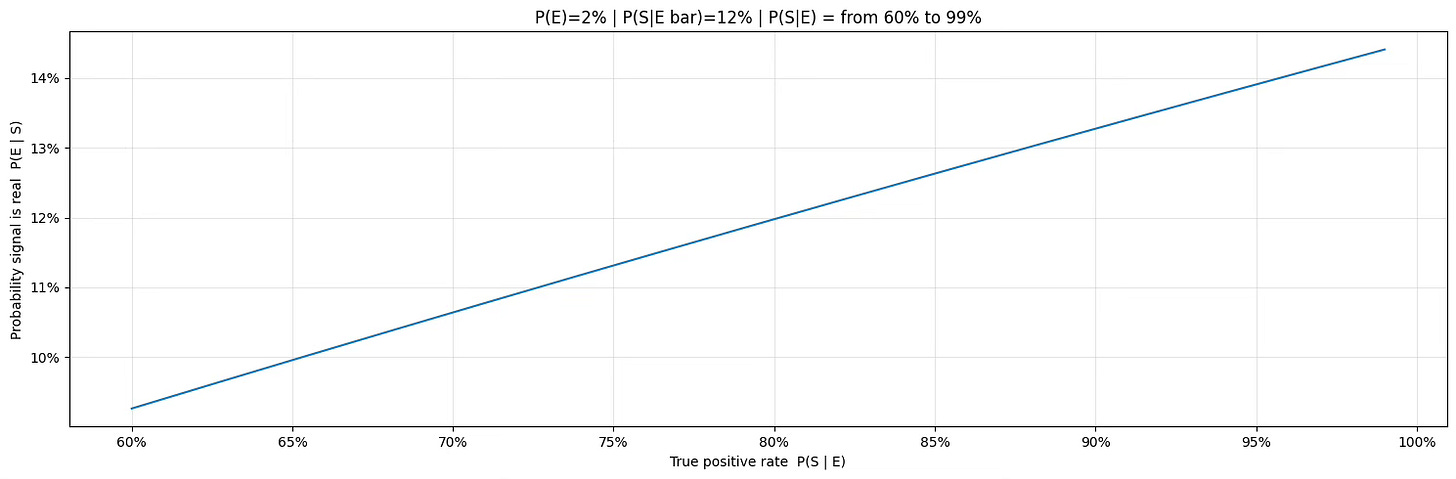

3. Accuracy helps, but far less than expected

In this final experiment, we vary only the detection accuracy of the model.

The event frequency is fixed at 2%, and the false positive rate remains at 12%, exactly as in the previous sections. Only P(S∣E) is allowed to change.

The improvement is real, but modest. Even large increases in detection accuracy translate into relatively small gains in the probability that a signal is actually correct.

This is a direct consequence of event rarity and persistent noise.

This explains why strategies that aggressively optimize accuracy often fail to deliver meaningful improvements in live trading.

Accuracy is rarely the dominant lever in rare-event strategies.

Conclusion. What to remember

For rare events, accuracy is not the right metric.

Signal quality is driven first by false positives, then by event frequency.

Detection accuracy helps, but far less than most people expect.

A strong model can still produce mostly noise if the base rate is low.

Bayes is not optional. It defines the ceiling of what a signal can achieve.

Before trusting any trading signal, always ask:

How rare is the event?

How often does the model fire when nothing happens?

What is the resulting probability that a signal is actually correct?

If these questions are not answered explicitly, the signal is likely misleading.

👉 If you want to go deeper into each step of the strategy building process, with real-life projects, ready-to-use templates, and 1:1 mentoring, that’s exactly what the Alpha Quant Program is for.